Restoration: Sunbeam 350hp

Submitted by:

BLUE THUNDER

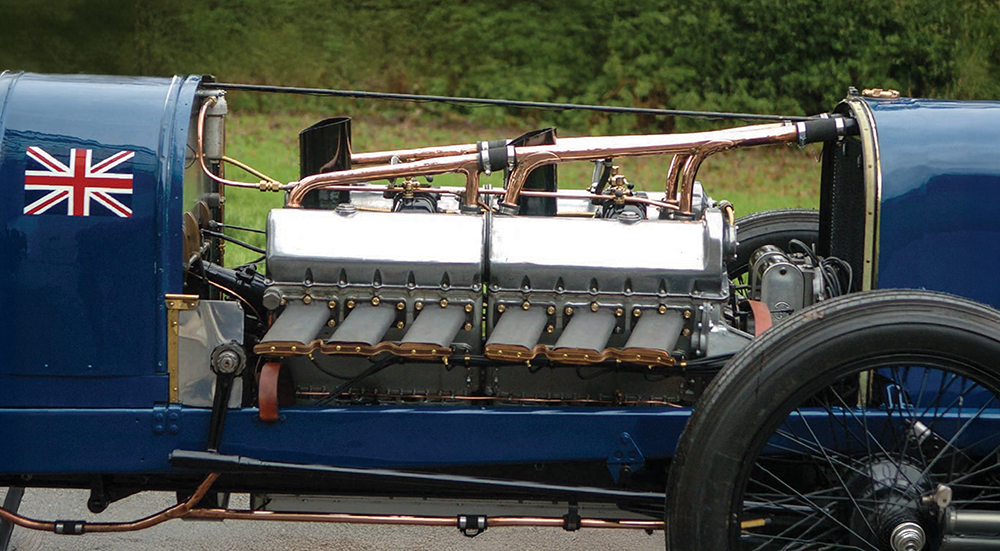

Now endowed with a replacement gearbox worthy of its role, the fully rebuilt 18.3-litre V12 engine of the 1925 land speed record-breaking Sunbeam 350 hp will now be capable of being driven dynamically.

The National Motor Museum at Beaulieu has recently completed the restoration of Sir Malcolm Campbell's record-breaking 350 hp Sunbeam, with the long-awaited installation of a replacement gearbox, following the complete rebuild of the original V12 engine which took place in 2014.

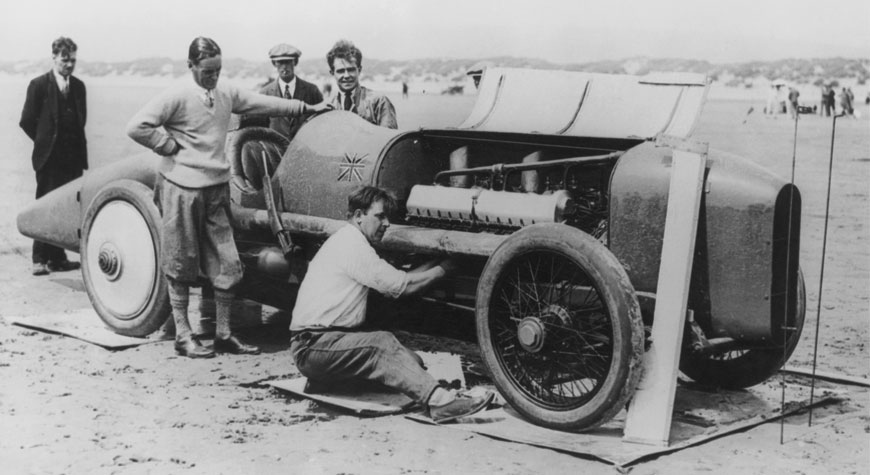

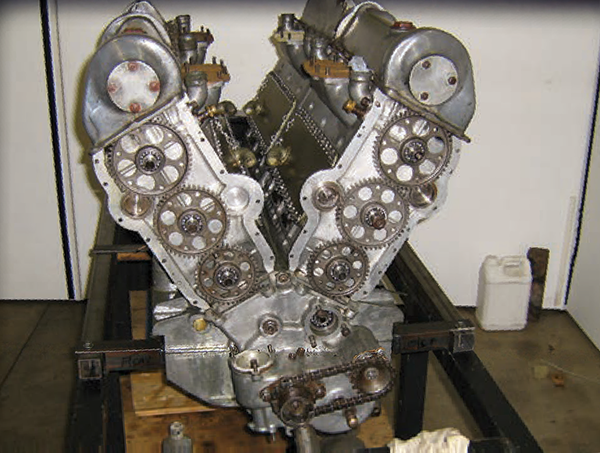

This car dates from the period following the first great war, when the world of motor racing was dominated by a number of racing cars powered by huge aircraft engines. One of the most famous was the brainchild of Sunbeam's chief engineer and racing team manager Louis Coatalen, constructed at the company's Moorfield works in Wolverhampton during 1919 and early 1920. It was powered by a modified 18.3-litre V12 engine, a hybrid derivative of the Sunbeam Manitou and Arab aero engines that were used on naval seaplanes.

Little more than the powerful drivetrain mounted within a simple channel section frame chassis, the Sunbeam race car had a four-speed gearbox with a drive shaft to the back axle with differential, rather than the hazardous chains used by other cars of the time.

As was usual during the period, the braking system was rather crude, with just a foot brake acting on the transmission and a handbrake on the rear drums. Suspension was by half-elliptic springs at both front and rear, damped by Andre Hartford friction shock absorbers.

It subsequently embarked on a long and eventful career in various disciplines of motorsport, achieving several land speed records, although its first outings were far from distinguished. It suffered a puncture and crash in practice for its first race at the 1920 Whitsun Brooklands meeting, driven by Harry Hawker. Then, following repair and recuperation, a stalled engine at the August meeting meant that the Sunbeam couldn't start its race.

Things improved later that year when it was taken to the Gaillon Hill Climb in France, where René Thomas took the course record with a 108 mph (173.81 kph) run on the 1-kilometre hillclimb course.

It was next driven for the first time by Kenelm Lee Guinness, at the 1921 Brooklands Easter meeting, achieving second place in the Long Handicap event, and then again at the Autumn, in both the Short and Long Handicap races. In the latter event Guinness finished in second place, achieving a speed of 140 mph (225.31 kph) and completing the last lap at an average of 116 mph (186.68 kph).

In May 1922, Guinness set three records with it, taking the Brooklands lap record at 123.30 mph (198.43 kph), then the land speed record over a mile at 129.17 mph (207.88 kph) and over a kilometre at 133.75 mph (215.25 kph). These were the last land speed records to be set on the Brooklands track.

Guinness raced the Sunbeam again at Brooklands in the autumn of 1922, before it was borrowed by Malcolm Campbell in order to compete in the Saltburn Speed Trials in 1923. He achieved a speed of 138 mph (222.09 kph), although - as this was only a one-way run and with a manual stopwatch timing system - it was not recognised as an official world record.

June 1923 next saw Campbell at Fano in Denmark where he registered another record-breaking speed of 137.72 mph (221.64 kph) over the flying kilometre, but again the record wasn't accepted because the timing equipment wasn't officially approved.

Intent on a serious record attempt, Campbell then purchased the car outright and commissioned aircraft builders Boulton & Paul at Norwich to design a new body for it, with the coachwork carried out by Jarvis & Sons of Wimbledon.

Following wind tunnel tests, the car was streamlined with a narrow radiator cowl at the nose and a long tapered tail, disc covers were fitted over the rear wheels, and the engine compression was raised with new pistons. Now painted in Campbell's trademark blue colour scheme, it was renamed 'Blue Bird', making it the fourth incarnation of that name.

Campbell returned to Fane in the summer, but on the first run both rear tyres ripped off and narrowly missed onlookers who were lining the course.

Campbell protested to the officials about crowd safety standards but, sadly, on the subsequent run a front tyre came off and killed a boy in the crowd.

Full of regret but undeterred, in September 1924 Campbell took Blue Bird to the beach at Pendine in South Wales to register a new official record speed of 146.16 mph (235.22 kph).

Soon making plans to build a new record-breaking car that would be capable of even greater speeds, Campbell advertised the Sunbeam for sale at £1,500 but with not much interest in it from other drivers, and with other rivals snapping at his heels, Campbell decided to retain it for one further attempt.

Returning to Pendine in 1925, on July 21 it raised the record to 150.766 mph (242.628 kph), the very first time a car had officially exceeded 150 mph (240 kph). In fact the best run over the mile had reached 152.833 mph (245.961 kph), a figure that appeared in contemporary adverts for oil and spark plugs.

The car subsequently passed through various owners, and appears to have returned to circuit racing with wider tyres and a return to the short tail with green paintwork. As late as 1936, it was owned by band leader Billy Cotton who drove it to a speed of 121.50 mph (195.53 kph) over a kilometre on the beach at the Southport Speed Trials.

The car seems to have remained in Lancashire during World War 2, before it was acquired by Harold Pratley in 1944 and was then loaned to Rootes Ltd (successors to the Sunbeam Company) and following a cosmetic restoration it was used for promotional purposes, usually transported and displayed on the back of trailer.

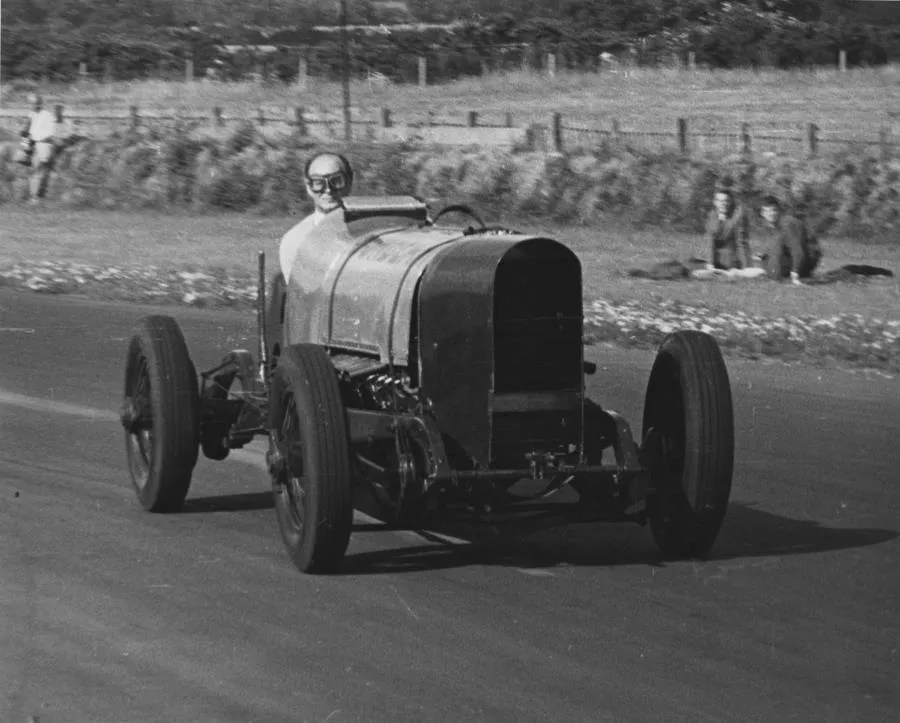

In 1957 the car passed into the care of the Montagu Motor Museum, where it was restored to working order and subsequently driven by Lord Montagu in various events both here in the UK and in Europe, and in 1960 it accompanied Lord Montagu as a static display on a lecture tour of South Africa. Its last outings were at Oulton Park and at the BARC Festival of Motoring at Goodwood in July 1962 when Lord Montagu took it on a demonstration run and Donald Campbell did a lap of honour.

Subsequently subjected to a gradual restoration process, in 1987 the car was repainted and the wheels rebuilt, and in 1972 it moved into the newly created National Motor Museum where it has been on display ever since, alongside other famous Land Speed Record holders.

Unfortunately, while assessing the car's condition, a test fire-up of the engine in 1993 resulted in seizure. A blocked oil way due to congealed old Castrol R oil caused it to throw a rod combination, with the slave rod twisted through 90 degrees, badly damaging the crankcase and sump.

The car was subsequently displayed in the museum, clearly showing the hole in the crankcase where the piston and connecting rod had lashed out.

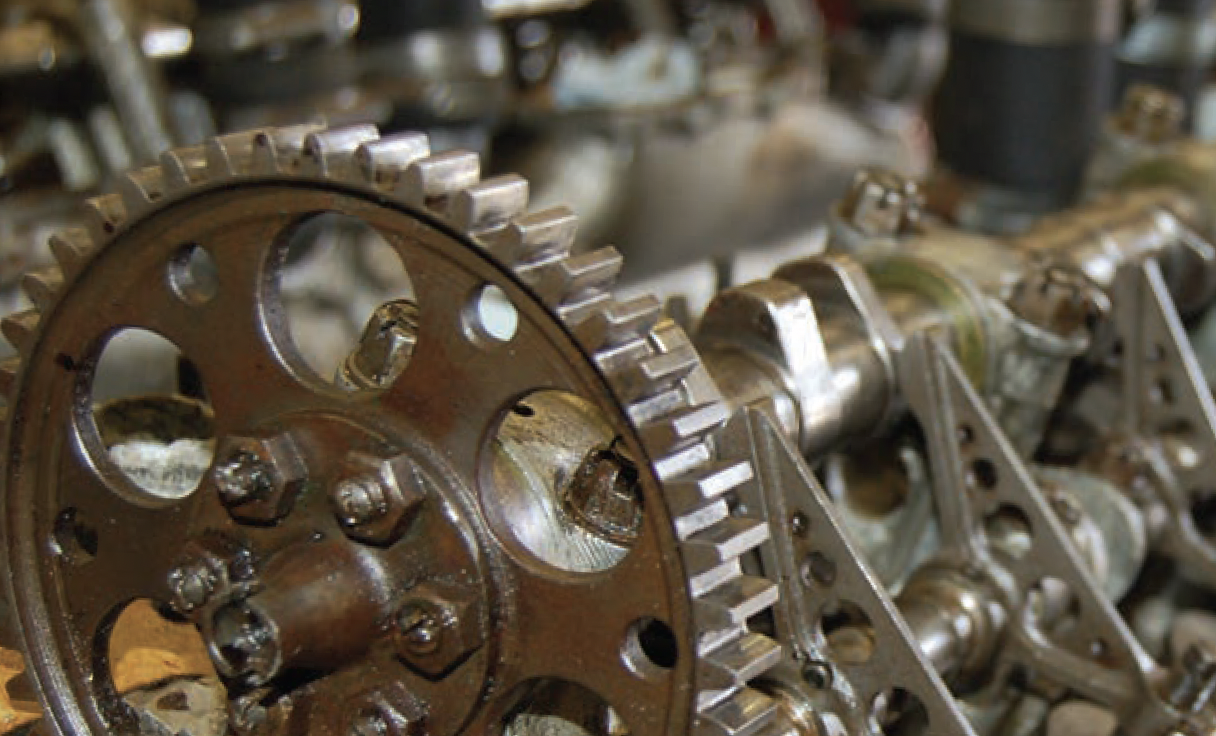

Around 2007, the workshop team started looking at the car with a view to repairing the engine and an initial strip-down allowed them to assess the damage sustained in the 1993 start-up. Examination showed that the con rod had come through the side of the crankcase, scoring the crankshaft and damaging three pistons and valves.

Amazingly, the most badly damaged piston was found inverted in the bore which, luckily, wasn't too badly damaged. Fortunately, the substantially supported 7-bearing crankshaft showed only minor bending, which was easily remedied.

Interestingly, further subsequent investigation also showed that one of the camshafts had an end cap missing which, if the engine had been allowed to run for any longer, would have resulted in major loss of oil pressure and would undoubtedly have caused extensive damage to the complex valve gear.

The Sunbeam Talbot Darraca Register was approached to assist in finding the parts, specialist services and skills to undertake the rebuild. A restoration of this size is a very time-consuming process, involving around 2,000 hours on this project, so the museum workshop relied heavily on a team of volunteers, directed by the workshop's Senior Engineer, lan 'Stan' Stanfield, along with workshop manager Michael Gillett, and also on generous donations by specialist suppliers.

As part of the engine rebuild, the damaged crankcase metal was stitched, the crankshaft re-ground and polished and the damaged cylinder bore re-lined. Damaged con rods, pistons, valves, springs, gudgeon pins and white metal bearings were replaced with new items and the main bearings were re-metalled and line-bored. The rear axle was also taken apart and thoroughly cleaned of all the congealed oil, and the chassis and running gear were completely renovated.

Doug Hill, the National Motor Museum's Chief Engineer, said at the time: 'This project has been a long-running labour of love for the whole team and such has been their passion that many have dedicated hours of their own time to get the job done.

There is huge satisfaction in seeing it finally completed'.Interestingly, further subsequent investigation also showed that one of the camshafts had an end cap missing which, if the engine had been allowed to run for any longer, would have resulted in major loss of oil pressure and would undoubtedly have caused extensive damage to the complex valve gear.

The Sunbeam Talbot Darraca Register was approached to assist in finding the parts, specialist services and skills to undertake the rebuild. A restoration of this size is a very time-consuming process, involving around 2,000 hours on this project, so the museum workshop relied heavily on a team of volunteers, directed by the workshop's Senior Engineer, lan 'Stan' Stanfield, along with workshop manager Michael Gillett, and also on generous donations by specialist suppliers.

As part of the engine rebuild, the damaged crankcase metal was stitched, the crankshaft re-ground and polished and the damaged cylinder bore re-lined. Damaged con rods, pistons, valves, springs, gudgeon pins and white metal bearings were replaced with new items and the main bearings were re-metalled and line-bored. The rear axle was also taken apart and thoroughly cleaned of all the congealed oil, and the chassis and running gear were completely renovated.

Doug Hill, the National Motor Museum's Chief Engineer, said at the time: 'This project has been a long-running labour of love for the whole team and such has been their passion that many have dedicated hours of their own time to get the job done.

There is huge satisfaction in seeing it finally completed'.

Then, on January 29, 2014, the Sunbeam was fired up again, the first time it had been heard in public in over 50 years - a sound which described as being akin to the roar of a Rolls-Royce Merlin engine. The following month it was a star of the show at Retromobile, Paris and was also run at the Goodwood Festival of Speed.

On July 21, 2015 - the 90th anniversary of Sir Malcolm Campbell's first world land speed record in 'Bluebird' - the Pendine Sands beach in Wales saw a low-speed demonstration run by the restored car, driven by Malcolm's grandson, Don Wales, himself an accomplished land speed record holder with vehicles as diverse as a lawn mower and steam-powered and electric cars.

The proviso here was that, although the engine had been fully repaired, the original gearbox had been removed at some time after World War II and subsequently lost, only to be replaced - presumably as a temporary measure - with a gearbox that was originally used in an Albion 35 hp van. Not only was it designed to take just one tenth of the power that the 18-litre V12 engine produces, but this gearbox also lacked a transmission brake, an important part of the Sunbeam's original brake set-up, meaning that this installation severely compromised the braking of the vehicle!

Next task was the launch of an appeal to raise funds to build a new gearbox. As Doug Hill explained 'For the next stage of the Sunbeam's restoration story, we needed to build a new gearbox from scratch. As the original gearbox no longer existed and there was no template to follow, with all original drawings and records lost when the Sunbeam factory was bombed during the war, this was a challenge requiring all of our knowledge and expertise. It was a vital step in our journey to restore the car to its 1925 specification and will greatly help us to drive the car closer to the speed it was built for.' With help from the museum's supporters, a sturdy Bentley C-type gearbox has since been sourced and adapted to fit the Sunbeam's chassis with custom-made mounts. This unit has proven, in other applications, to be well suited to the task of handling the substantial power output of the 18-litre V12 engine. Best of all, it enabled the engineers to install a robust and historically correct transmission brake and propshaft.

The installation of the new gearbox also required the fabrication of two full-length exhaust pipes, and a new seat and upholstery, the re-manufacture of a slightly dropped nose cone and rear wheel spats brought the car back to its original 1924 / 1925 record-breaking specification.

Hopefully, we'll now see the car driven dynamically again at events during the coming year, although it can usually be seen on static display at the National Motor Museum, as part of a multi-media presentation which also features its record-breaking stablemates the 1927 Sunbeam 1000 hp, 1929 Golden Arrow and 1960 Bluebird CN7.

The National Motor Museum's collection of over 280 vehicles is world-famous, along with its extensive range of motoring artefacts, photographic images, specialist reference library and film and video library.

For more information about its collection and services see www.nationalmotormuseum.org.uk